As your deep tech company’s research labs grow, you will gradually build a list of best practices. You will build new test equipment according to agreed-upon processes, buy parts from approved vendor lists, and have experienced engineers review your work.

However, research teams generally don’t love documentation. Your vendor lists will grow dated, your processes onerous, and your team fragmented. Your team may recognize the problem and get on top of the standards, but it will inevitably slip again. Entropy is the only truth in this universe.

What do you do?

Take a step back. What’s the point of having standards? Why do standards naturally form in research labs, and why do they always undergo cycles of creation and decay?

Standards exist to unify how a team works. Your team may not always have the cleanest approved vendor lists, but your team must always agree on the basic concepts underlying your standards.

If your team shares the same philosophy, you will find the sweet spot of productivity without documentation.

With that in mind, I’d like to propose a basic philosophy for building laboratory equipment.

To build a laboratory effectively, we must consider five interconnected goals: Safety, Simplicity, Consistency, Maintainability, and Flexibility. These goals come from years of experience working with builds throughout their life cycle - setup, operation, maintenance, and decommissioning - and experiencing the amplifying effects of early design choices on long-term maintenance.

It takes less time to do a thing right than it does to explain why you did it wrong.

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Chemistry labs work with toxic gases, high pressures, flammable liquids, and more on a daily basis. As such, safety is the core goal of all builds.

This topic is detailed in HS&E processes present at any well-run chemical research organization. Stripping the noise away, our biggest safety enemies are becoming complacent, moving too quickly, and misjudging risk.

In becoming complacent, we all become less aware of the risks around us as we continue to work with specific hazards. This leads to not treating the hazard with respect, ultimately leading to an unsafe event if not corrected.

In moving too quickly, our focus on completing equipment builds on time and under budget can lead to taking shortcuts. These shortcuts add up and pose risks that may not be easy to uncover.

In misjudging risk, we can underestimate a hazard and not adequately control for it. We can also overestimate hazards, building overly complex systems that blind us to major underlying issues (failure to see the forest for the trees).

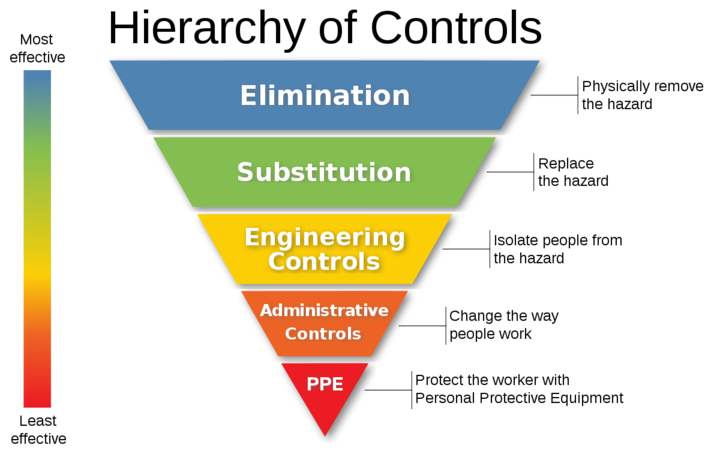

These are complex problems that involve both people and processes. For builds, we must follow the hierarchy of controls to establish redundant layers of safety.

This is the correct pecking order for responding to identified safety vulnerabilities. Believe it or not, this simple order often erodes at large and small companies alike.

Why is this? Simply put, people grow accustomed to living in the least effective part of the pyramid. Elimination and substitution will often get pushback from people looking to maintain experimental integrity, and engineering controls can be complex and expensive. What’s left is the bottom of the pyramid: administrative controls (ie. writing training documents) and PPE (ie. wearing a respirator). We must all continually challenge each other to prioritize the more effective solutions - even if they are more challenging.

Of particular note to equipment building is engineering controls, or the practice of modifying a build to be safer. We should prefer physical controls (ex. pop valve) over software controls (ex. ladder logic) and must use physical controls over software controls for high-priority items.

Examples:

An engineer knows perfection has been achieved not when there is nothing left to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.

- Antoine de Saint-Exupery💬There are tons of great quotes on simplicity from many memorable people. This link alone references quotes from Einstein, Jobs, Buffett, Da Vinci, and more. I chose this quote because it’s stuck with me for being so specifically targeted to engineering challenges. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (side note: he’s fascinating) was a pioneering aviator talking specifically about airplane design. He was decrying complex manufacturers, who were notorious for documenting each rivet on their airframe while failing to address the fundamental problem of engine reliability.

We constantly run into the same challenges with building equipment. Complexity is often the result of following the path of least resistance, or of doing things that feel helpful without zooming out and challenging that belief. We must all be mindful of the complexity trap and push each other toward simplification.

Keeping builds simple is critical to every goal on this list. Simpler designs build faster, cost less, and avoid diluting important safety issues with trivial details.

Much like safety, simplicity is easy to support in theory but difficult to follow in practice. In build design, complexity creeps in with too many reviewers and not enough pushback (ie. bikeshedding). In build modification, it comes in as modifications for one-off experiments that are never undone. Fortunately, there are specific practices we can follow to reduce the drift toward complexity.

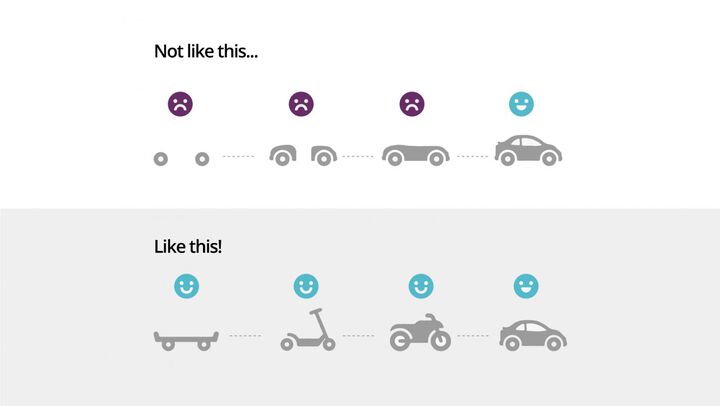

We must follow a minimum viable product workflow.

Determine the minimum requirements to get the immediate job done and build to only that. Be strict here! The most valuable data you will get is not from your first design review, but rather from operators using your first-revision build. Your goal is to build them a simple system, measure success by talking with operators, and then design the next revision.

We must push back against features that add complexity without offering real improvement in the designed use. These features (ex. improved operator usage, non-critical sensor redundancy) are often better included as an upgrade instead of part of the initial design.

Finally, we must remember to continually simplify equipment in operation. Disconnect unused instrumentation, remove excess wiring, delete obsolete ladder logic, and archive unnecessary code. (The best time to do these is during maintenance and upgrades… always strive to leave a build better than you found it!)

Simplicity is a fight against entropy, and joining in this fight is the only way you can maintain a large amount of custom equipment with a small team.

Examples:

A customer can have a car painted any color he wants… as long as it’s black.

- Henry Ford

Keeping vendors, parts, wire colors, instrument naming, and code styles consistent is critical for the long-term success of custom equipment. This has been proven time and time again, where equipment not built to a broader standard gets neglected over time and gradually falls into disrepair.

Building lasting equipment requires adhering to equipment and style standards. By doing so, more people know how to work with the equipment. As equipment inevitably changes hands throughout its life, others trained to the same standard will be able to understand, debug, and modify to suit their needs.

Consistency leads to many other perks. Better spare part inventories (reducing maintenance/down time), tried and tested interfaces with complex instrumentation (avoiding new quirks), and more salvage value in decommissioning will all help convert your build into a success story.

This all being said, it is important to also know when to break the rules. Most builds are ~90% consistent with hardware standards, drifting only when the benefit of a particular non-standard instrument outweighs the associated complexity. When these arise, flag them with your tem and be prepared to explain your reasoning.

Examples:

Extra features were once considered desirable. We now recognize that ‘free’ features are rarely free. Any increase in generality that does not contribute to reliability, modularity, maintainability, and robustness should be suspected.

- Boris Beizer

In a lab, successful equipment is modified far more often than it is built. As such, anyone designing equipment to last must think about how their design will hold up to years of modification.

Many of the topics here are covered in simplicity and consistency. Fewer components and consistent parts/naming make it easier for others to understand and modify the system. This is often the difference between equipment evolving with the company versus falling into disrepair.

In addition, equipment will tend to grow in complexity over time. You must account for this by providing enough space in your piping panel, control box, and software to account for unforeseen changes.

Examples:

A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.

- Ralph Waldo Emerson

The above goals push for equipment that is safe, simple, consistent, and maintainable. These are necessary goals, but we must avoid defaulting to a religious adherence to any standard (relevant Dogma).

Being an expert builder requires knowing when and how to break the rules. Remember that all the policies and procedures we have in place are only tools to get you to think about important issues. If a particular process is adding burden without living up to this goal, it must be called out and improved.

Philosophies are no exception. Standards must evolve over time as new situations arise, new technology is introduced, and new patterns emerge. If you ever disagree with anything, start a conversation with your team.

Examples: