If you’re in science or engineering, you’ve probably used equipment with data ports. In some cases, those ports are connected to nearby computers loaded with proprietary software (that only runs on Windows XP for some reason). When software can’t be found, the ports go unused. There’s a tiny LCD screen displaying a number, and maybe someone writes that number on a piece of paper every hour.

That has to feel wrong.

Fortunately, it only takes a few lines of code to write a functional interface. With the right skills, you could be remotely logging - and even controlling - your equipment in the time it takes you to finish your morning coffee.

Unfortunately, equipment manufacturers are a conservative bunch. Once they have an equipment design that sells, they’re not going to revise their design just to keep those data ports modern. This means that learning to talk to equipment requires familiarity with decades worth of older interfaces.

The goal of this post is to provide that familiarity. By having a mental framework that connects all of these interfaces, you’ll be equipped to teach yourself the field. You’ll be able to have opinions on purchasing decisions (“is an ethernet port worth an extra $100?”), third-party drivers (“can LabVIEW do everything we need?”), and rolling out your own software.

Here’s how I like to think about these things. Picture a tree:

Imagine each of its leaves as a communication protocol. Each leaf is labeled with something you probably haven’t heard of before today: 4-20mA, 0-10V, SPI, I2C, RS-232, Modbus RTU, Profibus, EtherCAT, ToolWeb, DeviceNet, BACNet, Modbus TCP, UDP, HTTP, and so on. The tree has hundreds of leaves because there are hundreds of protocols.

Some people spend their entire careers living in the leaves. They take classes learning how to handle industrial protocols one by one and make good money by knowing them. However, it’s memorization without understanding. That sort of knowledge doesn’t do well when confronted with new unknowns.

Beneath the protocol leaves are branches. Each branch is a concept. Smaller branches are the easier concepts that relate a few protocols. These merge into the larger branches of bigger concepts and then finally to the trunk.

Here’s the trick: if you know a branch, its leaves are easy to learn. If you learn a bigger branch, then its smaller branches are easy to learn. Once you understand the trunk, everything becomes easy. You may not know the whole tree, but you know how to teach yourself to get to a new leaf.

The goal is to get to the trunk. The challenge is that, unlike leaves, the trunk can’t be taught through terminology. It’s a concept, and it fundamentally has to “click” with the learner. For that reason, the best lessons start with smaller branches. Little concepts, taught with leaves as examples. With enough exposure, the bigger branches become easier to learn. One day, a student understands the trunk and the whole field becomes a simple exercise.

My goal with this post is to start building your tree. This tutorial doesn’t teach you how to do anything, but it should give you a framework that will help you learn that part yourself.

Let’s see what I can do here.

Electronics are hard to visualize. Electrons, current, voltage, and the like aren’t tangible and can complicate other concepts. To explain this field, I want to re-imagine electronics as they would be in a post-apocalyptic steampunk world.

Here’s the scenario: zombies. The zombies can be styled to your preference (I prefer Shaun of the Dead), but the point is things are bad. You’re trying to survive.

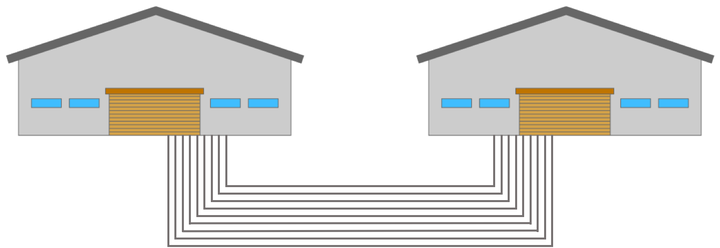

You and a small group of survivors have built a makeshift camp in an old warehouse. One day, you come across another group living in a warehouse a few miles away. They’re friendly, and you decide to work together for your mutual benefit.

Your first task is to establish communication. You start sending people to the other warehouse to discuss the day’s news. One day, one of the communication parties doesn’t come back. There are zombies out there, after all.

While thinking through ways to communicate, you find that many old pipes connect the two warehouses. Maybe you could use those for something?

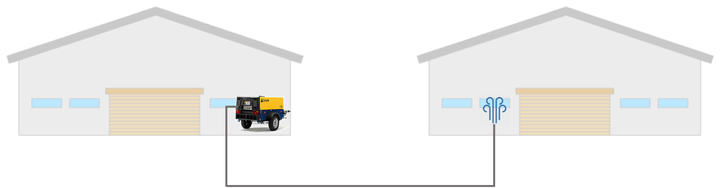

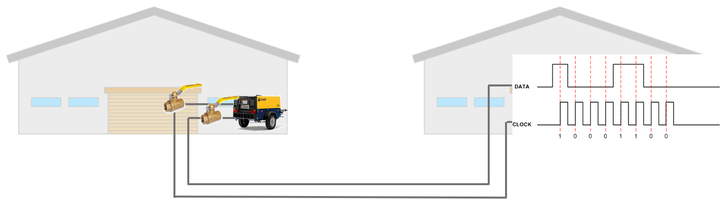

You look around your commandeered warehouse and find a working air compressor. You think about it for a minute and realize that you could use the compressor to blow air through a pipe. You decide to do this and see what happens. When the day’s communication party returns, they report that a pipe in the other warehouse started going berserk. Perfect.

The next day, the communication party tells the other warehouse to label the pipe as HELP. If it’s blowing air, it’s because you’re doing it. And, when that pipe is blowing, it means that they should send help.

Congratulations, you just established real-time communication.

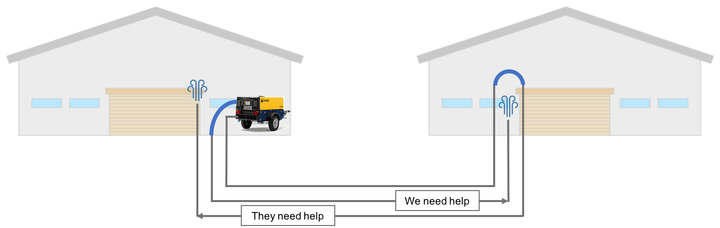

This works for your needs, but the other warehouse is getting annoyed at the one-way nature of the setup. You can tell them when you need help, but they can’t tell you when they need help! That doesn’t seem fair. You ask them to get their own compressor, but they can’t find any. Maybe there’s something you could do to solve this?

Out of the blue, you think up a brilliant solution. You tell them to put a cap on the end of one of their pipes. Your air compressor will keep that pipe pressurized. If they’re in trouble, they can replace the cap with a joint and send the pressurized air back through another pipe. This will indicate that they need help. You label the corresponding pipe on your end HELP, and you’re in business.

You’ve stumbled upon the relay. Well done!

Fast forward a couple of months, and you now use relays for everything. You still have pipes devoted to HELP, but now you have hundreds of pipes in use. There are pipes for FOOD, WATER, SICK, and AMMO. Emoji pipes started popping up - HAPPY, SAD, BORED. Someone even made a tic-tac-toe game, and the league’s getting competitive. Life is good.

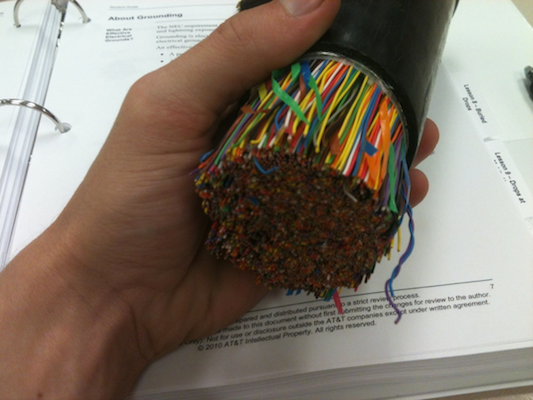

Like your zombie warehouses, control engineers did the same thing. Once engineers discovered relays, they got used everywhere. The reasoning is simple. Relays were the first good-enough solution that people could reliably use to control equipment. Sure, expressive communication required hundreds of wires, but people just bundled them all together.

Relays are simple, and they’re second to none when it comes to speed and reliability.

Your relays are working great, but your communication parties are still going out every day. You’ve sped up key communication, but you haven’t solved your original problem!

They’re going out because some data can’t be easily communicated over the relays. They want a daily inventory of people, supplies, ammunition, and more. This is critical data, as the growing towns can trade to their mutual benefit.

The problem is that relays can only be off or on. They can’t send values. With your past success, you’re now the de facto communication engineer. It’s on you to figure out a solution.

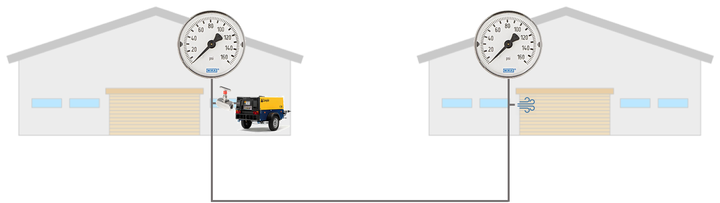

After some time at the drawing board, here’s what you come up with: you’ll use the pressure of the air to send quantitative data. You have valves and pressure gauges kicking around, so you just need to screw these onto the pipes. You’re in business. Your compressor provides air at 100 psi, so you set a pressure scale to communicate data. For the PEOPLE pipe, you decide that 0 psi means 0 people, and 100 psi means 1,000 people. It scales linearly between the two. Easy. You do similar things for AMMUNITION, FOOD, WATER (upgrading the old relays here), and it kind of works.

This is good, but pressures on the low end are confusing. Does 0 psi mean that there’s no water, or does it mean that they’re just not communicating at this moment? You decide to revisit your scale. Now, 10 psi means 0 people, and less than 10 psi means that communication is down — an easy upgrade.

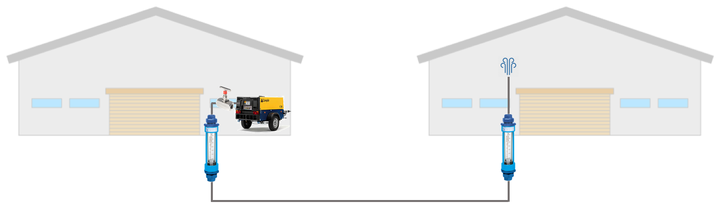

One other issue is that the pressure read on the other side is slightly lower than the pressure on your end. You realize that this is due to the pressure drop throughout the pipe. Minor, but annoying. You decide to fix it. Rather than going off of pressure, you tell people to switch to flow rate. Regardless of the pressure, flow in must equal flow out.

On the next iteration, people swap out their pressure gauges for rotameters. You set the scale to 4-20 LPM, and now the other side sees exactly the value you’re putting through the pipe. Problem solved.

You’ve discovered analog communication. You can now communicate with numbers, which is far more expressive than the simple on-off of relays. Your communication parties no longer go out daily and instead spend their time hanging out with you. You put them out of a job, after all.

Back to the real world. Analog communication was (and continues to be) very important in industrial controls. It allows richer communication than relays and enables significant automation. For example, temperature can be controlled by toggling a heater relay until an analog temperature signal matches a desired value. Easier, safer, more controlled.

Analog still requires multiple wires and lacks many features, but it’s simple and it works.

Despite the zombies, post-apocalyptic life is going pretty well. After inventing analog, you got promoted to Director of Communications. You sit in on steering committee meetings, and everyone respects your technical acumen… even if they can’t quite explain what it is you do. You now have a team under you, and maintenance is easy. Things are just working.

One morning, you’re with your team running through some math. Communication is going pretty well, but it does use an awful lot of pipes. A lot of pipes means a lot of air. You now have hundreds of pipes transmitting data, and peak communication loads are wearing on your air compressor. If you want to keep operating, you’re going to have to turn something off or risk losing the one piece of equipment keeping this whole thing going.

You call an emergency meeting of the steering committee, but they don’t understand. Compressors? Pipes? It’s too technical. Everything’s working now, so why wouldn’t it work in the future? So much for steering committees; it’s on you to figure this out.

How do we do anything better here? Is there a way to communicate more information with less pipes? You and your team are brainstorming, and someone remembers Morse code. That’s that thing where people used dots and dashes to communicate over a wire. Could we do the same with compressed air?

You’ve just entered the digital age.

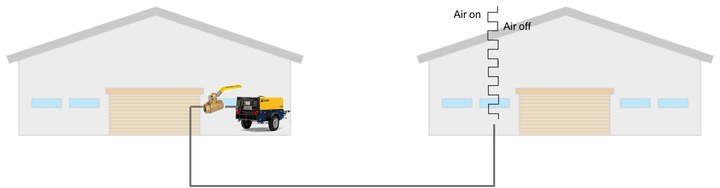

The first thing you realize is that dots and dashes are slow. Instead of DOT and DASH, you want to use OFF and ON. You figure that will be much faster.

As shorthand, you call OFF “0” and ON “1”. Each signal is a “bit.” It makes sense to you.

To start, you want to see if you can fit all of your relays into a single pipe by using this. You have hundreds of active relays, and each is only sending one bit of data. If you can string them all together, i.e., 0100001111011001111, and if the other side knows the order of the bits, then this should work. Hundreds of pipes reduced down to one!

Excitedly, you tell your team and they go on an expedition to tell the other warehouses. They’re in. You set up a pipe and start trying it out, and it sort of works.

There’s potential! You’re excited, but the luddites are fighting you. “It’s not as reliable!” they say. “It’s way too complicated!”. They don’t see the bigger picture. Hundreds of pipes reduced to one. Your air compressor no longer anywhere near peak capacity. You choose to ignore the naysayers and keep going.

Back to the drawing board. Why is your new digital protocol only “sort of” working?

The first annoying part is that communicating the binary protocol is a pain. Wouldn’t it be much nicer to have actual conversations with any sort of data you want? That has to be possible, right?

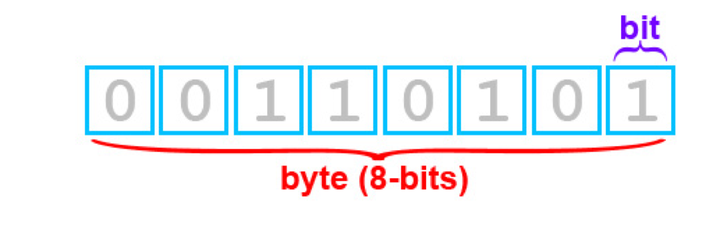

You start figuring out what this would look like. You go on to decide that every 8 bits is a “byte.” Each byte will encode a single letter. Enough bytes and you have real words.

You randomly make up an encoding that happens to exactly match the pre-apocalypse standard of ASCII.

| Byte | Letter |

|---|---|

| 01100001 | a |

| 01100010 | b |

| 01100011 | c |

| … | … |

| 01111010 | z |

Wow, what are the chances?

As an example, if you want to send “hello,” you’ll toggle the air like so:

h e l l o

01101000 01100101 01101100 01101100 01101111

You can have full-text conversations now! You give out your bytes-to-letters conversion table freely, and now both warehouses are fluent.

One of the younger engineers asks how you can extend this to communicate in Chinese. You tell her to go away.

A couple of years from now, you’ll regret this choice.

The other warehouse is having a hard time figuring out the speed at which you’re toggling the air. Are you sending 010 or 001100?

You decide to use a different pipe as a “clock.” It’ll go 1010101010 so long as it lives and can be used to time the data pipe properly. You can even give the other side control of the clock pipe, so they can switch it when they are ready.

If you want to say “hello,” your two pipes now look like:

h e l l o

data: 01101000 01100101 01101100 01101100 01101111

clock: 10101010 10101010 10101010 10101010 10101010

After reducing everything down to two data pipes and a clock pipe, you’re starting to dislike the clock. When you were simplifying hundreds of pipes, you had pipes to spare. Now, you’re so close to being down to a pair of data pipes. Why aren’t you?

You decide to do away with the clock pipe and instead standardize the speed at which you’ll communicate.

Your team’s been working on some systems to automatically “read” and “write” the bursts of air, and they’re able to reliably toggle the air 9600 times per second. You distribute your automated reader and writer designs, tell everyone else you’ll be sending data at 9600 bps (bits per second), and then try it out.

It works, but it’s a little finicky. Everyone set their devices to 9600 bps, but they’re all built out of shoddy parts. Some are operating a little faster, some a little slower. Over enough time, those small differences add up. The clocks go out of sync, and everything falls apart. You think up a quick fix: send some bits at the beginning and/or end of each byte. When those are read, the 9600 bps counters will reset. That way, the drift won’t be able to build up as data is collected.

If you want to say “hello” but end every byte with a 1, it now looks like:

h e l l o

011010001 011001011 011011001 011011001 011011111

You have to send a little more data, but that’s one less pipe to worry about.

After some usage, you notice that not all pipes are created equal. Some can’t keep up with 9600 bps, so you reduce them to 4800 bps. Others work great, so you increase their rates to 19200 bps. However, both sides still need to know what rate to target. Wouldn’t it be great if this could be automated?

Well, you can already communicate any data you want through the pipe. What if, when you start using a pipe, you send the pipe’s maximum speed? You agree to send this data at, say, 1200 bps, but once the other side knows the rate of transmission, you can ramp to full speed. Great! You no longer have to keep track of the speed of each pipe. You can even update the speeds if something changes.

You’re starting to realize that communicating data about the connection has a lot of potential. Little do you know that you’re barely scratching the surface.

The data’s really starting to flow. This system was built for vital communication, but that’s starting to feel like an afterthought. With all the spare capacity, people are constantly sending texts, developing new multi-player games, and generally socializing with the other warehouse. Someone is even making their own encoding for sending pictures.

However, one-bit errors pop up every so often. Most of the time, the errors are meaningless. “How’s the weather?” turns into “How’s the %eather?”. However, you recognize that it does run a risk. “Send help” could transfer as “send kelp,” for example. That’s unfortunate.

Your team recommends that you keep the old-fashioned relays active for the really important stuff. You agree, but you also want to get to the bottom of this reliability issue.

You come up with an idea: When you send a message, you’ll calculate the number of air puffs (“1”s) that make up the message. At the end of the message, you’ll send this number along. On the other side, they’ll cross-check that they got the same number of 1’s as you. If they didn’t, they’ll ask for the message again.

If you want to send “hello,” it now looks like:

h e l l o 21

01101000 01100101 01101100 01101100 01101111 00010101

You just created a checksum. This helps significantly, but the occasional malformed message still gets through.

You’re convinced that better checksums exist. There’s a mathematician on your team now, and you task him with thinking about this problem. He comes up with a more complicated checksum, but the idea remains the same. With his algorithm, miscommunication becomes a thing of the past.

For short messages, your system works great. But, longer messages prove problematic. There are many more chances for a longer message to get muddled - you only need a one-bit error for the checksum to fail! You notice that people aren’t sending longer messages because they don’t want to deal with the headache of re-sending data. Instead, they’re sending the message in smaller chunks, and then the recipients are rebuilding the message on the other side.

That’s smart. You decide to standardize it. Every 40 bytes will be a “packet,” and you get your team to build a device that automatically splits and recombines packets. Large-message data reliability goes up without much effort.

With this, you also notice that the stop bits are no longer needed. By breaking a message down into smaller packets, the clocks don’t have enough time to fall out of sync. And, if a read error occurs, it’ll get caught in the checksum anyway.

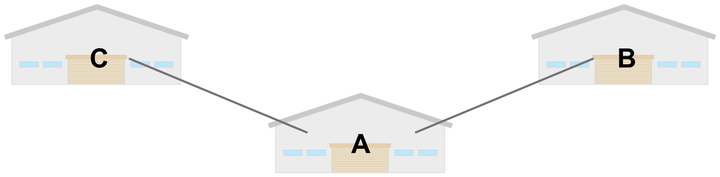

An expedition from a third warehouse finds you, and you discover that they’re also connected by pipes. You excitedly tell them about all of your communication development, and they’re interested. You implement the same setup with them.

You decide to name the warehouses Alpha, Bravo, and Charlie.

You tell Bravo about Charlie, and they want to communicate. Not a problem. You’ll forward messages on their behalf. Here’s the plan: the first two bytes of data will contain the sender and the recipient. Alpha is A, Bravo is B, Charlie is C.

Sending “hello” from Alpha to Bravo now looks like:

A B h e l l o

01000001 01000010 01101000 01100101 01101100 01101100 01101111

If you receive a message with B or C as a recipient, you copy it down the line.

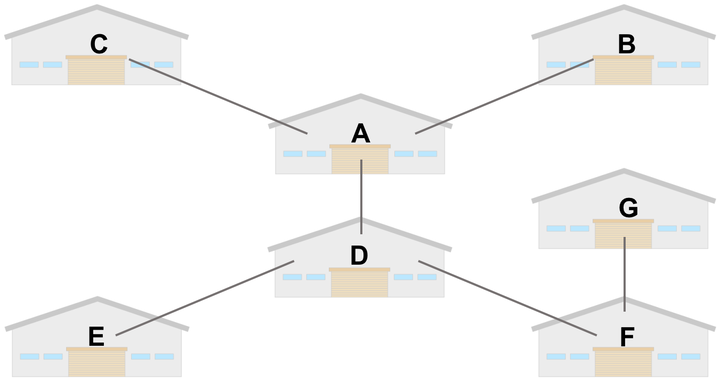

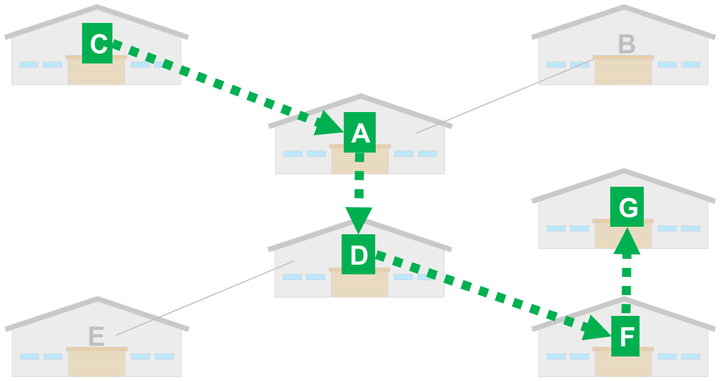

After organizing this, you meet another warehouse. You call them Delta. Delta tells you that they have pipes connected to two other camps: Echo and Foxtrot. They get on the network, and Foxtrot tells you they’re connected to camp Golf, who also wants to join. It seems that some of these camps know further groups. This is getting complicated.

You know the network topology, or how people are connected. If you get a message addressed “CG,” you know to forward it to Delta. Delta will forward it to Foxtrot, and Foxtrot will finally send it to Golf.

You can draw this out, but you’re starting to realize that this is going to be big. Hundreds, if not thousands, of camps may want to communicate through this network. You need an automatic way to figure out the network topology.

You send a series of requests to every other camp. In each request, you ask them who they’re directly connected to. You rebuild this data and use it to help you forward things. However, you realize that everyone needs this data for communication to work. It can’t all flow through you.

You expand the addressing header. If the address destination is set to 0, then the message is for everyone. When someone gets a message with a 0, they read it themselves and also send it to everyone they’re connected to. You use this to solve your problem. Everyone sends their neighbor connections to everyone else, and the network operators at each camp can piece it all together.

Saying “hello” to everybody now looks like:

A 0 h e l l o

01000001 00000000 01101000 01100101 01101100 01101100 01101111

You warn people to use these sparingly. They require everyone to communicate, and too many could take down the network.

At this point, you realize you have a functioning steampunk internet.

After a few months, the network has grown to hundreds of users. Communicating with complete strangers has become commonplace, and there’s a growing distrust. Camps Bravo, Charlie, and Delta were personally vetted, and you met a couple of people from Golf that seemed normal. However, you’ve never met anyone from many of the other camps, and you want them to forward your messages without being able to read them. Is this possible?

After sending the source and destination, you decide that you’re going to invert the second half of each byte. Send a 1 when you mean 0 and vice versa. You tell your friends but leave the middlemen in the dark.

With this, sending “hello” to Golf looks like:

A G h e l l o

01000001 01000111 01100111 01101010 01100011 01100011 01100000

A G g j c c `

You send “hello,” but middlemen see “gjcc`.” They think you’re speaking gibberish, but your recipient will know what to do with it.

Your mathematician finds you and tells you that this isn’t “cryptographically secure.” He recommends a really complicated algorithm. It does the same thing, but it’s much harder to decrypt. He says you can even teach everyone the standard without risking getting personally decrypted.

Everyone buys in, and now everyone’s sending encrypted data.

One day, Golf runs into a camp that’s, well, different. They’re connected on their own digital network, but they don’t use any of the standards you’ve built. You figure it’s not an issue. You just need to translate between the two networks, and then the connection can be made.

You learn that they represent letters as 7 bits, not 8. They translate between bits and letters differently, and they don’t have any addressing capabilities, checksums, or encryption. You’d rather get them up to your more modern standards, but their Director of Communications doesn’t care. Their standard works, after all.

You learn how to send and receive data over their protocol, and your engineers build a translator that can interconvert in real time. You discuss the design with Golf, and they build one. The networks are connected.

A couple of weeks later, you meet another camp with a similar issue. However, their Director of Communications is sketchy. He was a salesman in the pre-apocalyptic world, and he quickly realized that communication was worth money. He has his own protocol, but he won’t teach you how to read and write it. He instead wants to charge you for an integrated reader/writer device. He tells you that Delta already bought one, but they’re forbidden from building a translator to connect to a broader network. The salesman’s goal is to own the protocol and make people to pay him to use it.

This goes against everything you built! Communication should be free! You don’t buy the reader, but you can still log the 0s and 1s from the salesman’s camp. You have a team of engineers log this data. They eventually find patterns and, not beholden to the salesman’s contract, reverse engineer a converter. You let everyone on your network know that if they want to talk to this camp, they can do so for free through you. The salesman goes out of business, and the internet remains free.

Fast forward a year, and your network now contains thousands of camps spanning hundreds of miles.

Communication is so important that disconnected camps are laying their own pipes.

Someone figured out that twisting two pipes together significantly increases communication speed, and new installs are reliably transmitting data at over 1,000,000,000 bps. With gigabit speeds, one of the camps figured out how to send and receive real-time video. The border camps have been broadcasting live video streams, keeping everyone current with zombie movements.

Thanks to your network, an entire region has banded together to manage the zombie threat. The future’s looking bright.

You may not know all the terminology yet, but with this background, you should now be able to classify protocols according to their features. This is commonly done by going through the OSI model, but don’t worry about that yet. Instead, let’s try a few: